|

| A rider during a public bikes trial in Bogotá a few years ago. |

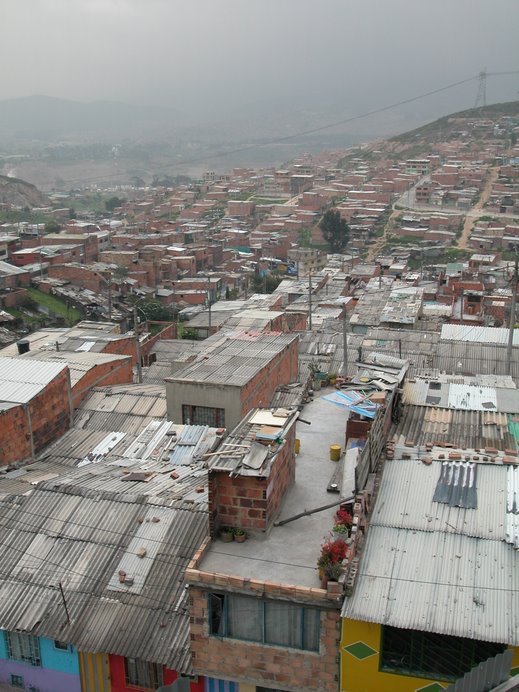

Bogotá, D.C.'s per-capita income is less than U.S. $20,000.

The conclusion? Washington is a much, much, richer city and Washingtonians have lots more spending power.

Washington also receives many more tourists than does Colombia's capital and has better streets and less crime.

So, now guess which of these two capital cities is subsidizing its public bikes program, and which one expects those bikes to pay a profit to the city?

If the answer made any sense, then I of course wouldn't be writing this commentary.

Last week, Bogotá finally chose a company to operate Bogotá's planned public bicycles program. Cycling advocates should be celebrating, and would be, if the scheme didn't have all the signs of disaster.

The Colombo-Chinese consortium, Bicibogotá, consists of a garbage collecting company and a home appliance company, neither with any experience in bicycles. And it's Colombian owner has a history of corruption and other scandals.

But those difficulties are minor compared to the fatal flaw in the city city's approach to creating a long-awaited public bikes program. Other cities see their public bike systems as public services which improve health and reduce air pollution and traffic congestion and subsidize them. But Bogotá expects its public bikes to pay the city profits.

Washington D.C. subsidizes its Capital Bikeshare program, as does Vancouver, Canada; Melbourne, Australia; and the U.S. cities of New York; Chicago; Minneapolis; and Chattanooga, Tenn. Toronto, Canada, Toronto, Canada decided not to subsidize its own bikesharing program. But, despite being a much wealthier city than Bogotá, its program was struggling as of 2013. Even mega-wealthy New York's Citi Bike program will be in crisis if sponsor Citibank pulls out.

And the numbers get even worse from there, as this graphic from the Washington Post shows.

In Washington, as the first circle shows, only about one fifth of users are locals who buy annual memberships. The rest pay by the ride, and are presumably mostly tourists. The second circle shows that the annual members do the great majority of the riding. However, the third circle shows that casual riders pay almost two-thirds of the program's revenues.

Bogotá, besides being a much poorer city than Washington D.C., also receives far fewer tourists, meaning that its revenues will be far lower.

Is this contract only Mayor Petro's desperate effort to create a legacy, at whatever cost? Does anybody believe that public bikes can work in Bogotá without a subsidy? Why launch a program doomed to failure, which will only leave a black mark on cycling here?

Instead, Bogotá should take the route of almost every other city and see bicycling as a public benefit, which cleans the air, reduces traffic jams and improves people's health, and subsidize cycling.

This is particularly true, after all, since dirty transport receives, albeit often invisible, subsidies.

By Mike Ceaser, of Bogotá Bike Tours