|

| This week, environmentalists held this protest in La Candelaria against apartment construction impacting the Conejera wetland in Suba. |

|

| A view of the Conejera wetland. (Photo: Humedales de Bogotá) |

But builders may have gone too far with an apartment building in Suba, which environmentalists say would impact the La Conejera wetland (the name means 'rabbit hutch'). Young people staged a camp-in against the project, and local residents have marched in protest in both Suba and Bogotá.

Environmentalists say the apartments would frighten off wildlife (obviously true, especially since residents will have dogs, cats and children), and generate noise, light and water pollution. The prosecutor's office visited the construction site and pointed to various irregularities, including the construction license having been issued 'in record time' and that the license had first been rejected and then issued.

A bit strangely, perhaps, Bogotá Environment Secretary Susana Muhamad defended the project, saying it has all its necessary papers.

|

| A bird in the Conejera wetland. (Photo: Humedales de Bogotá) |

Amidst all the legal wranglings, no official appears to have the interest or authority to say that this project is bad for Bogotá's long-suffering environment and should be stopped.

Hanging over the debate - and probably the only reason this project has received attention at all - is the fact that the construction company's board of directors includes several relatives of Bogotá Mayor Gustavo Petro. Petro says his administration has shown no favoritism and that the license was issued by a previous administration.

That corruption played a part is not unthinkable. In Bogotá, construction licenses are issued by strange offices called Curadurias, which have a dubious reputation for corruption. Petro's predecessor, Samuel Moreno, is in prison on corruption charges unrelated to this project.

|

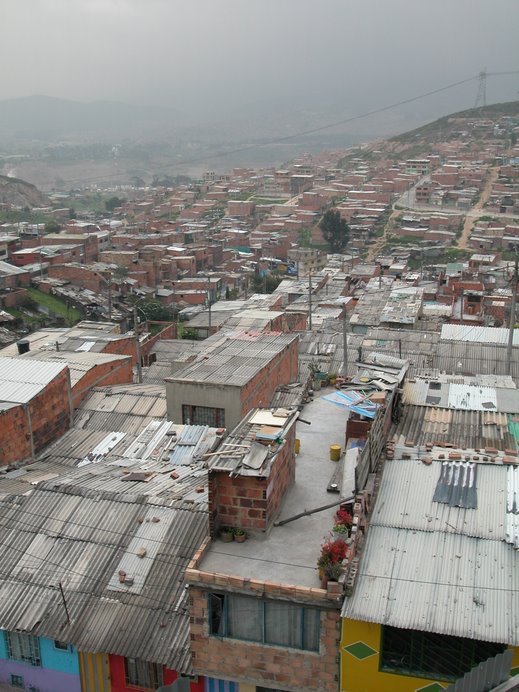

| Environmentalists this week protest apartment construction impacting the Conejera wetland in Suba. |

|

| An areal photo from RCN Noticias shows construction apparently invading the Conejera wetland. (Photo: RCN Noticias) |

By Mike Ceaser, of Bogotá Bike Tours