|

| Inmates in Bolivia's San Pedro Prison. (All photos taken by Mike Ceaser, around the year 2000.) |

|

| Children in San Pedro Prison. |

Thomas McFadden would have been just one more guy doing time in a Third World prison for trying to make fast and easy money smuggling drugs - except that McFadden got locked up in La Paz, Bolivia's hyper-corrupt San Pedro Prison and befriended Australian lawyer-turned-writer Rusty Young.

The result,

Marching Powder, is a memorable account of McFadden's years in San Pedro. Marching Powder may not match the grueling prison accounts like Papillon and Midnight Express, but it does capture the craziness and corruption of Bolivia and San Pedro prison - where prisoners hold the keys to their own cells, manufacture cocaine and sometimes sometimes do prison tours for foreigners.

And Marching Powder, of course also provides an implicit commentary on the War on Drugs.

|

| In San Pedro's kitchen. |

|

Rusty Young during a visit

to Bogotá two years ago. |

From the book's beginning, when McFadden is betrayed by a police official whom McFadden has bribed to let his cocaine shipment thru, to the book's end, when McFadden pays off judges to let him off of a trumped-up drug charge, this book is about corruption. I lived for several years in Bolivia and visited San Pedro Prison multiple times, and throughout the book I kept telling myself: 'Yep, that's Bolivia!'

|

The prison's swimming pool. McFadden describes an

episode in which a mob murders three alleged

child rapists in this pool. |

San Pedro, with its stores, families, churches and neighborhood organizations, is arguably a more humane place to be locked up than many normal prisons - A french drug trafficker and mercenary doing time there told me 'This would be the world's best place to be imprisoned - if you could only get your sentence.' Indeed, the prison seemed to be full of inmates who'd spent years there without being getting their trial, much less sentence - one of the disfunctional systems' myriad arbitrary and wholesale human rights violations. McFadden's experience starts with him being thrown into a cell and forgotten, apparently a strategy meant to force him to confess, then later deposited in San Pedro, where he crawled into a bathroom to sleep and was beaten up by other inmates who believed that he was from the U.S. (the country which inspired Bolivia's hated drug laws).

|

| A prisoner relaxes in his cell. |

|

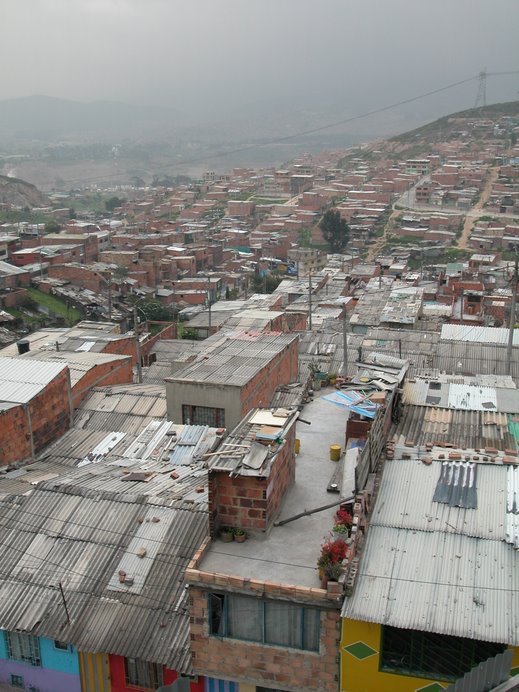

| Clothes drying in crowded San Pedro Prison. |

After his initial crisis, McFadden actually flourishes in prison. Marching Powder drew me in with its accounts of McFadden's entrepeneurial efforts in prison, including opening businesses, operating criminal projects and doing tours for foreign tourists. At one point, McFadden even finds work in a prison cocaine factory in order to 'keep myself out of trouble.' But prison was all fun for McFadden. His conflicts with other inmates, particularly the evil Fonsecas, and the tragedies of unfortunates shipped off to die in the cold and barren Chonchocoro prison in the altiplano, are also gripping. But I could have used less about his love affair with an Israeli tourist, which wasn't so different from a love affair anywhere. On the other hand, I would have appreciated much more about other inmates: their crimes, their backgrounds, their roles in Bolivian society. When I visited San Pedro a decade ago, I recall hearing accounts of campesinos doing long sentences because a small plot of coca bushes, the base ingredient for cocaine, had been found on their land. In some cases, the drug crop may not even have been theirs. Others, called mulas, had been caught transporting small packages of drugs, from which someone else would make most of the profit, but they'd pay any penalty. These sorts of impoverished people are the ones who get trapped by the system, railroaded, and end up living in San Pedro with their wives and families.

|

A French mercenary works on art in his cell

in San Pedro Prison. |

|

| In San Pedro's carpentry shop. |

This prompts me to ask what ends imprisonment in San Pedro Prison achieves: Does it punish criminals? Protect society from criminals? Preserve human rights? It's hard to argue that it accomplishes any of these things, altho it clearly does provide great criminal training and ruin lots of lives. Does Bolivia's penal system fight crime, and the drug trade specifically? Sure, McFadden suffers in prison - but he keeps on dealing. (The book at times reads like a how-to manual for drug smugglers). And, for every smuggler that gets caught, many must successfully bribe or sneak their way thru and enjoy the profits. On the other hand, San Pedro is full of people doing time for petty offenses or none at all, simply because they are poor and powerless. All of this at huge human and financial costs for an impoverished nation.

While reading Marching Powder, I also wondered about the experience of the author, Rusty Young, a young Australian lawyer, whom I met in Bolivia (where he struck me as too much of a cokehead to ever write a book), and again here in Bogotá. Young gets portrayed as something of a hero in the book for helping McFadden beat a second, trumped-up charge and finally leave prison. I would have enjoyed a chapter describing Young's own impressions first-hand: It's not every day that a lawyer from a rich nation pays to spend time in a corrupt third-world prison.

|

| Lunchtime in San Pedro. |

And I spent much of the book wondering about McFadden's own background: Was his family poor? Rich? How did he get into drug-smuggling? Why? What happened to all the money he must have made? McFadden evidently had a long exprience running drugs to Europe, but he provides no details. Perhaps he left this out for legal reasons, altho it seems as tho the years and statutes of limitations would make earlier crimes irrelevent. This lack is the book's single greatest failing, in my opinion.

|

| The source of the trouble: Coca bushes. |

It's hard to feel very sorry for McFadden, who made quick money thru bribery and smuggling an addictive substance knowing full-well the possible consequences. While incarcerated, McFadden got the assistance of the British consulate and a UK prisoners' rights organization, was aided by friends back home and got the love of a beautiful Israeli girl - not to mention plentiful and cheap cocaine and marijuana. That many people who've committed no crimes at all should be so lucky!

|

| A La Paz graffiti says 'Don't fall asleep - chew coca.' |

I also looked unsuccesfully for some remorse or reflection from McFadden about his trafficking. He says that before San Pedro he'd never tried cocaine, a claim which seems dubious (but if true is another condemnation of the prison system). McFadden seems to have enjoyed San Pedro's plentiful drug supply, altho without those daily highs he might have used his prison time more productively, perhaps by studying something. In San Pedro, he witnesses pathetic cases of drug addiction - just as he must have seen in the outside world. Yet McFadden never reflects on the human impacts of his profession, and in fact continues shipping drugs from prison.

|

| Headed to San Pedro? A Bolivian coca farmer whose plot has been erradicated. |

Naturally, I also wonder what McFadden is doing today. I suppose that if I had to guess, judging by his long experience and his continued success smuggling drugs while in prison, I suspect he might back at his old profession.

With its imperfections, Marching Powder is an interesting and entertaining book which will open your eyes.

|

| Protesters, many of them coca farmers, in Cochabamba, Colombia. |

|

| Protesters, many of them coca farmers, march in Cochabamba, Colombia. |

|

| Schoolgirls in San Pedro. |

By Mike Ceaser, of

Bogotá Bike Tours